Cracked Everyday Life: Thoughts on Kick That Habit, a film by Peter Liechti

[Published in Andy Guhl: Ear Lights, Eye Sounds on Edizione Periferia, 2014.]

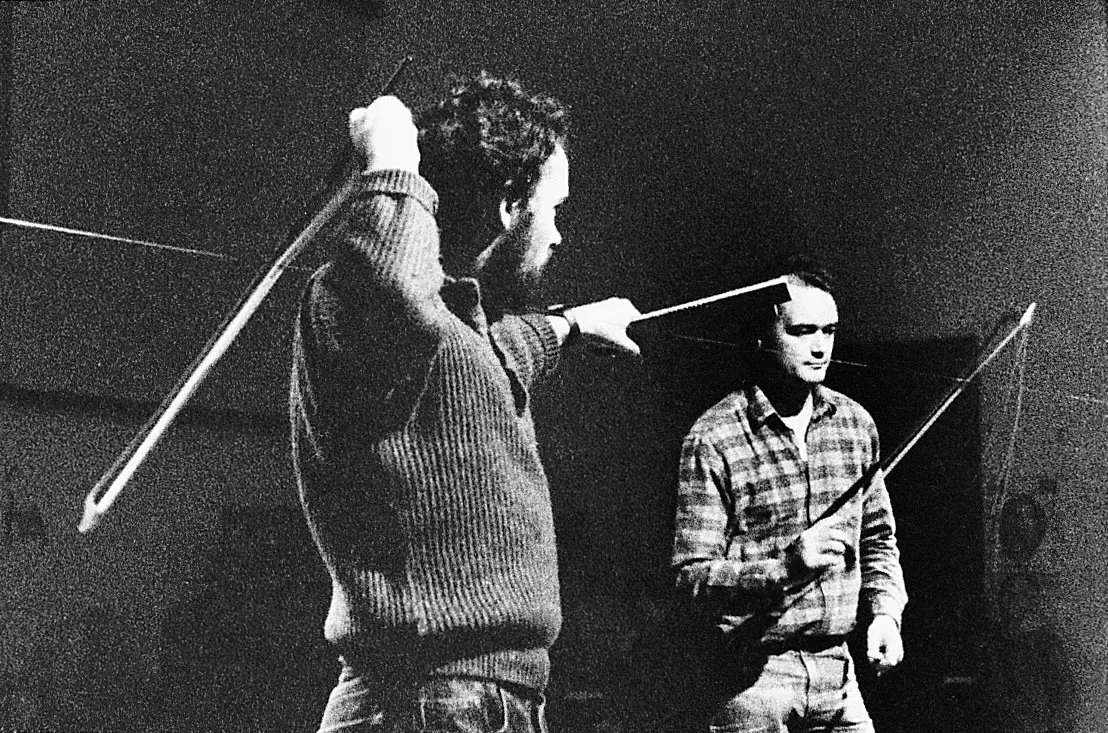

Swiss musicians Andy Guhl and Norbert Möslang formed the duo Voice Crack in 1972, originally performing entirely acoustic improvisation on reed instruments and percussion, then gradually incorporating electronics into their performances until they were eventually performing electronics exclusively. Voice Crack uses the phrase “cracked everyday electronics” to describe their constantly shifting and growing instrumental resources: familiar sound-making devices such as turntables, tape machines, and radios; piezo contact microphones; long wires strung across rooms and played with violin bows and sticks.

By the late 1980s, Voice Crack was a primary moving force in the popularization of low-cost, low-fidelity electronics as source and instigator of improvised sound making. In Peter Liechti’s 1989 documentary Kick That Habit, Guhl, Möslang, and their collaborators are shown performing in concerts and room-sized sound installations; but from the very beginning the movie focuses on the musicians’ engagement with creating sound in their everyday lives, often in a puckish manner. The members of Voice Crack are shown actively engaging with their sonic environment of their small town in Switzerland and making it their own. Many of these pedestrian sound making activities are filled with performative intention: little clusters of rhythm and gesture, reminiscent of rock drumming, rather than simply activating a medium and allowing it to sound itself. In the DVD, their sonic/performative engagement with the environment is made even more idiosyncratic by their unglamourous settings - trailer parks and scrap metal yards - set against the visually stunning backdrop of the Swiss Alps.

The opening of the movie shows Voice Crack playing on a miniature golf course for the sake of exploring the sounds made by the course’s various tricks and traps. In another scene, the duo and their friends are seen sitting around a dinner table, the act of serving and eating food highly amplified by piezos and room microphones. The meal is reminiscent of John Cage’s 0’00”, in which the performer undertakes any organized action, highly amplified. But it is both more and less than that. Voice Crack doesn’t seem interested in anyone’s instructions about how to amplify to the quotidian. They play openly with the distinction between performance and concept - contact microphones and noise circuits are built into pieces of fruit as they are being served; cups are slammed dramatically on the table after drinking in a way that suggests both a hearty toast and a guileless, even obtuse, performative action.

This kind of homespun approach to making one’s own sounding environment within the existing environment, using redeployed and makeshift objects, can be traced at least as far back as Pauline Oliveros’ reworking of her home recording studio into a room-sized instrument, soup ladles and all (e.g. 1959’s Time Perspectives). With Voice Crack we see a move towards portability of means, a continuous process of accumulating and shedding sonic resources as materials become available and the practitioners’ interests wander intuitively, with improvisation as the dominant mode of practice. A performer of the sound environment has taken on a new role of managing how the components of the environment interact, finding new intersections, and exploiting the potentials of those interactions. No longer expected to be the master of one tool, s/he has taken on a new role of managing how the components of the built environment interact, finding new intersections, and exploiting the potentials of those interactions. The performing musician's domain shifts from tool user, to tool maker, to environmental engineer.